Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement learning approach to strategic game behavior

Context

The Robotics and Mechanisms Laboratory (RoMeLa) participated in RoboCup, an international robot soccer competition with different leagues and robots in order to promote robotics and artificial intelligence research. We entered the Adult-Sized Humanoid (ASH) League where four adult-sized humanoid robots autonomously play a game of soccer against each other in a 2v2 format. The autonomous robots are required to sense the environment, make decisions, and act based on the decisions to achieve victory. A camera and an inertial measurement unit (IMU) were used for sensing. The sensor information obtained from the camera and the IMU is proccessed to localize the robot, other robots, and the ball in the environment. The processed information is used to make strategic decisions to win games. I developed a strategic game planner based on the subsumption architecture to make timely and informed decisions. I also decided to try a reinforcement learning approach as well.

Reinforcement Learning

While it was simple and straightforward to develop basic behaviors and organize them into an augmented finite state machine to make tactical decisions, the behaviors were crafted based on heuristics, which was time consuming, and human estimation, which is often sub-optimal. There is also no way to evaluate the different behaviors, requiring human judgement instead of a systematic method to decide on which behaviors to keep and which to remove. Reinforcement learning could be used as an approach to quantitatively evaluate the effectiveness of the emergent behavior. Due to the success of reinforcement learning algorithms in board games, such as Chess and Go, and even video games, such as Super Mario and Starcraft, reinforcement learning was explored as a game strategy module. Further success was found in an application of reinforcement learning to a bipedal robot to perform complex behaviors by synthesizing dynamic motions, showing feasibility on real-world. Thus, reinforcement learning is explored as a method to make tactical decisions for a bipedal soccer robot. To do so, it would need to observe the positions of itself, the ball, and the opponents in Cartesian space, resulting in a eight dimensional observation space.

A baseline scenario (Figure 1) was defined and developed in a simulation environment to compare reinforcement learning and finite state machine approaches. The environment was built based on the real field dimensions. The scenario starts with the player starting in a random position on the left side of the field and the ball placed in the center of the field. The scenario ends when the ball is kicked into the opposition’s goal. The time taken to complete the scenario is averaged over multiple trials to measure the performance of each approach. The standard deviation of the time taken over the multiple trials is used to measure the consistency and reliability of each approach. Below is an example of the scenario.

Q-Learning

A basic Q-learning algorithm was first used to train a robot in a grid-based world to kick a ball into the goal. The initial attempts at using Q-learning showed promise, but the algorithm quickly ran into the curse of dimensionality. The algorithm managed to reach ending conditions when the observation space was four dimensional (positions of the robot and the ball), but immediately struggled when the grid was expanded from a 9 by 14 table to 18 by 28 table. In other words, the basic Q-learning algorithm using a grid-based world is not scalable. Furthermore, in order to produce quality decisions, it is necessary for the model to train on an environment that accurately represents the real world, so compromising for a simpler environment with fewer discrete spaces is not an option.

Deep Q Network

To deal with the challenges of dimensionality, Deep Q Network (DQN) was also explored. DQN is a model-free network that does not require its environment’s transition functions to make predictions of future states or rewards. Since the planner is correlated to building a planner for the actual soccer game, the RL model-free approach is expected to give a good robust solution. DQN is built on Fitted Q-Iteration, which uses different tricks to stabilize the learning with neural networks. I used stable-baseline3 library, which comes with a set of reliable implementations of Reinforced Learning algorithms. The DQN algorithm in this library has provided us with Vanilla Deep Q learning implementation.

The observation space is continuous, but the action space is discrete. A large amount of time was spent building a custom environment with strategically placed rewards to encourage certain behaviors such as getting closer to the ball and kicking the ball towards the opposition’s goal. Negative reward is accrued each time step to avoid making unnecessary repetitive actions. Due to time constraints, the task has been simplified to kicking the ball towards the opposition’s goal without any opponents. The opponents were removed from the observation space because designing collisions into the model was causing the agent to freeze in one position.

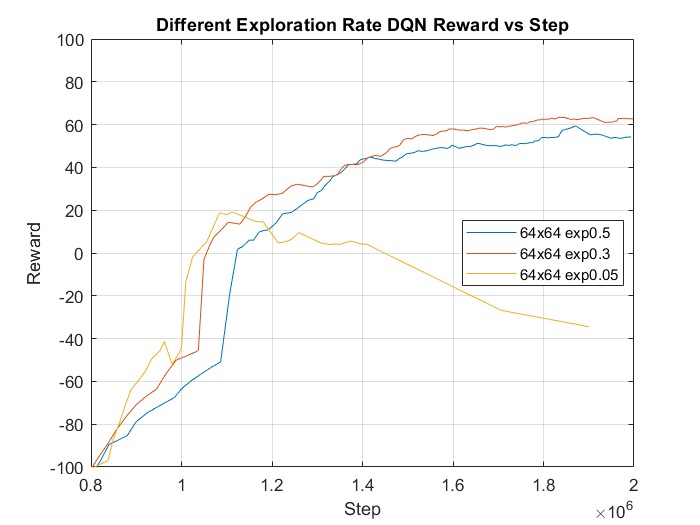

The final exploration rate influenced how robust and accurate the model was to different types of situations. A low final exploration rate produces a highly constrained action, but is prone to getting stuck in local optimas. A high final exploration rate would require exponentially more epochs, but would be more robust against local optimas. Different models with a final exploration rates of 0.05, 0.3, and 0.5 were trained and the exploration rate (Figure 2) with the highest reward was chosen.

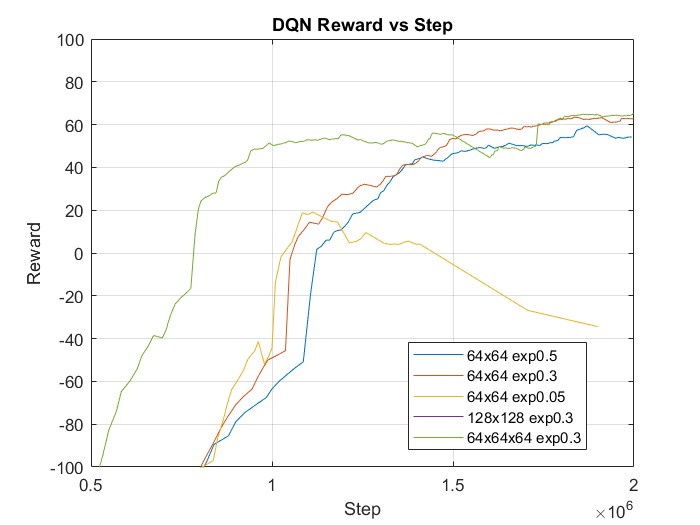

With a set exploration rate, models with different architectures were also trained (Figure 3). Modifications to the architecture were made because the scenario involves not only finding a path to the ball, but also interacting with it. Thus, more layers were added to represent the additional complexity. More neurons were added to the layers to better represent the states, but no significant performance boost was observed. The architecture that achieved the highest reward was chosen for the algorithm comparison.

The scenario was attempted multiple times by the Q-learning algorithm, DQN, and behavior-based algorithm developed from the game behavior module. The average time and standard deviation of completion time is summarized in the table below.

The two reinforcement learning algorithms performed similarly in terms of mean time and standard deviation, but did not do better than the behavior-based algorithm. The behavior-based algorithm achieved both the best performance (low mean completion time) and consistency (low standard deviation). It is clear that the behavior-based algorithm has proven to be the best solution to the baseline scenario. Some reasons why reinforcement learning may not have performed as well as other systems may be attributed to the fact that the network architecture may not have been deep nor wide enough to properly express the complexity of the test scenario. Most deep reinforcement learning applications in literature use either very deep or wide architecture, neither of which were done. Instead, the number of layers were restricted to just three layers with 64 units each in order to quickly iterate through more architectures.

References

2023

- Learning agile soccer skills for a bipedal robot with deep reinforcement learningarXiv preprint arXiv:2304.13653, 2023

- Development and Real-Time Optimization-based Control of a Full-sized Humanoid for Dynamic Walking and Running2023

2021

- Deep reinforcement learning based mobile robot navigation: A reviewTsinghua Science and Technology, 2021

- How to train your robot with deep reinforcement learning: lessons we have learnedThe International Journal of Robotics Research, 2021

2020

- “Robocup Federation Official Website.” RoboCup Federation Official Website, 26 Feb. 2023, https://www.robocup.org/.2020

2018

- Automatic goal generation for reinforcement learning agentsIn International conference on machine learning, 2018

- Learning by playing solving sparse reward tasks from scratchIn International conference on machine learning, 2018

2017

- Curiosity-driven exploration by self-supervised predictionIn International conference on machine learning, 2017

2013

- Playing Atari with Deep Reinforcement Learning2013

2003

- A proposal of a behavior-based control architecture with reinforcement learning for an autonomous underwater robot2003

1996

- Reinforcement learning: A surveyJournal of artificial intelligence research, 1996